The Complexities of Farmer Pricing Models

12 Jan 2022, by Admin in Harvest Against HungerEllis Fahsholtz serves as the Farm to Community VISTA at Harvest Against Hunger (HAH) in Seattle, Washington. Farm to Community is an umbrella that encompasses three of HAH’s farm to hunger relief programs, including Farm to Food Pantry, King County Farmers Share, and the PCC/NFM program. These serve to network between small farmers and food distribution organizations, with the goal of creating stronger local economies, and to uplift communities by reducing hunger, preventing food waste, and increasing access to healthy, local produce.

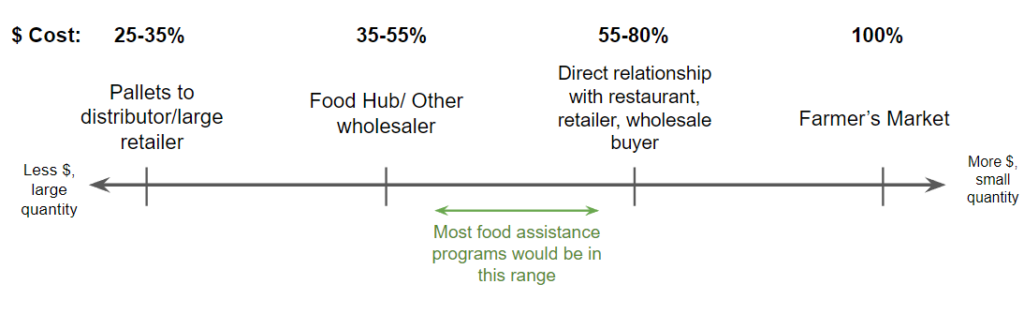

One of the most difficult hurdles facing new farmers is determining how they should price and market their produce. There are a vast number of factors to consider, and this task can be daunting without a good understanding of local markets and a decent amount of field research. Because of the nature of food pricing varies so much across geographical areas, it can also be challenging for agencies to give broad advice on the topic. However, it can be useful to think through these factors at play in terms of the kind of business new farmers want to run. Chris Teeny at Pacific Coast Harvest is currently working on a pricing system in progress, and his concepts inspired this simplified graphic from HAH’s info-sessions with Business Impact NW:

Farmer’s market prices are typically the most expensive, because it requires more transportation, labor, packaging, etc. alongside typically being a smaller amount of product. The diversity of crops for sale can also affect pricing. A good way to get an idea for what prices should be in your area is often to simply go to the farmer’s markets and see what the average prices are for different foods.

One step to the left on the diagram, at about 55-80% of the farmer’s market price, is produce sold in slightly larger quantities to smaller wholesale buyers such as restaurants or retailers. This often requires a larger variety of products with specific packaging, and delivery. Farmers will also have to spend a few hours per month maintaining business relationships, but this can be beneficial to the brand.

When working with food hubs or other larger wholesalers, the prices are typically 35-55% of the farmer’s market prices. This is a less personal relationship, the farmer might not directly know where the produce will end up being sold after being redistributed. It requires more consistent packaging, but sometimes can have shorter delivery routes as they may have their own delivery trucks. Food assistance programs purchasing from local farms typically fall in between these two categories of wholesalers, depending on the size of the organization.

The least expensive category is for the largest wholesale customers, who are typically purchasing pallets of produce at a time. Frequently, they can handle pickup/delivery themselves, and require standardized packaging before they are redistributed to retailers. Some of the largest food banks can fall into this category with common produce items, before they are sent out to smaller pantries.